Cadagon Guide to Morocco

Cadagon Guide to Morocco

Back to Cadogan Guides Overview

Back to Guidebook Series

Browse by Region

Cadagon Guide to Morocco

Cadagon Guide to MoroccoIf travel is a search for lost paradise, the Muslim Kingdom of Morocco is large and mysterious enough to infinitely prolong the quest. It has an exoticism all of its own, created by the conflicting influences that have washed against this northwestern corner of Africa. Whatever your experience of the latin temper of southern Europeans, the heady lifestyle of Morocco is more dramatic. From the moment you land adventure assails you. In simple transactions, like buying a kilo of oranges, there is unexpected drama, humour and competitive gamesmanship. Th sun is always shining somewhere in Morocco, and from March to October it is difficult to avoid. Travelling from the cool peaks of the Atlas mountains to the baking heat of a Saharan oasis, or from the city of Marrakech to a beach, is cheap and easy. You can fly, drive, take the train, or share the tempo of local life by packing into a communal taxi or bus.

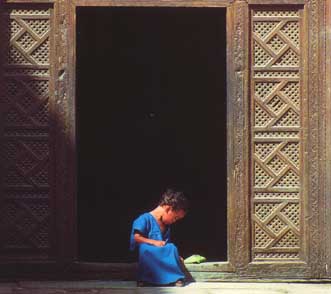

It is not only the sites of Morocco-the Roman ruins, the ancient cities, mountain kasbahs and elegant Islamic monuments-but also the everyday way of life that lingers in the memory: breakfasts of fresh coffee and croissants; the heavy odour of virgin olive oil; and the pyramids of fruit, vegetables and nuts which are so fresh and pure they seem like a new species altogether.

Morocco is a land fit for the jinn, full of extremes to reflect the changing whims and petulant egotism of proud spirits-high mountain chains, desert plains, long rivers, lush secluded valleys, broken wooded hills and undulating farmland. South from Tangier are the rich but flat and largely treeless agricultural provinces of the Rharb, Chaouia and Doukkala, punctuated by large coastal cities such as Kenitra, Rabat, Casablanca and Safi. East from Tangier the Rif mountains run along the Mediterranean coast of Morocco like a northern rampart against Europe. They reach their peak at Jbel Tidiquin, above the kif-growing centre of Ketama, and decline as they approach the Algerian border. To their south, fertile plains surround Fes and Meknes, and a thin strip of low land to the east-the Taza Gap-separates the highlanders of the Rif from those of the Middle Atlas. Beyond the citadel of Taza this brief gap in the mountains opens out into the wide eastern desert, the plains of Jel and the Rekkam. The Middle Atlas is an amorphous mountainous mass, a vast irregular limestone plateau whose ancient rounded summits dominate much of central Morocco. Three great rivers, the Sebou, the Moulouya and the Oub er Rbia, drain its forested slopes. To the south rises the much more intensely dramatic mountain range of the High Atlas, which extends east from the Atlantic coast for 700km (430 miles) and exceeds 4,000m (13,000ft) at the summit of Jbel Toubkal. The northern face shelters innumerable mountain valleys, wooded heights drained by fast flowing streams that create lush basins of fertility around the cities of Beni Mellal and Marrakech. The southern slopes of the mountains face the Sahara, and, though dramatically denuded, collect whatever rain falls and direct it south to create for 100km (60 miles) the astonishing oasis valleys of the pre-Sahara. The palm-shaded valleys of the Dades, Draa, Rheris and Ziz, overlooked by traditional settlements and in total contrast to the sunbaked arid mountains, create some of the most enduring and potent images of Moroccan travel. The Anti-Atlas range, next to the Atlantic seaboard, rises a clear 100km (60 mils) south of the High Atlas across the verdant Sous Valley, though at its east end the massifs of Siroua and Sarho merge their twisted barren slopes with those of the high Atlas. South of the last oasis villages of the Anti-Atlas the flat wasteland of the Western Sahara stretches immutably south; a harsh landscape that shows a 1000km (600 mile) face of savage cliffs to the Atlantic, broken by beaches at Tarfaya, Laayoune and Dakhla.

Morocco is a land fit for the jinn, full of extremes to reflect the changing whims and petulant egotism of proud spirits-high mountain chains, desert plains, long rivers, lush secluded valleys, broken wooded hills and undulating farmland. South from Tangier are the rich but flat and largely treeless agricultural provinces of the Rharb, Chaouia and Doukkala, punctuated by large coastal cities such as Kenitra, Rabat, Casablanca and Safi. East from Tangier the Rif mountains run along the Mediterranean coast of Morocco like a northern rampart against Europe. They reach their peak at Jbel Tidiquin, above the kif-growing centre of Ketama, and decline as they approach the Algerian border. To their south, fertile plains surround Fes and Meknes, and a thin strip of low land to the east-the Taza Gap-separates the highlanders of the Rif from those of the Middle Atlas. Beyond the citadel of Taza this brief gap in the mountains opens out into the wide eastern desert, the plains of Jel and the Rekkam. The Middle Atlas is an amorphous mountainous mass, a vast irregular limestone plateau whose ancient rounded summits dominate much of central Morocco. Three great rivers, the Sebou, the Moulouya and the Oub er Rbia, drain its forested slopes. To the south rises the much more intensely dramatic mountain range of the High Atlas, which extends east from the Atlantic coast for 700km (430 miles) and exceeds 4,000m (13,000ft) at the summit of Jbel Toubkal. The northern face shelters innumerable mountain valleys, wooded heights drained by fast flowing streams that create lush basins of fertility around the cities of Beni Mellal and Marrakech. The southern slopes of the mountains face the Sahara, and, though dramatically denuded, collect whatever rain falls and direct it south to create for 100km (60 miles) the astonishing oasis valleys of the pre-Sahara. The palm-shaded valleys of the Dades, Draa, Rheris and Ziz, overlooked by traditional settlements and in total contrast to the sunbaked arid mountains, create some of the most enduring and potent images of Moroccan travel. The Anti-Atlas range, next to the Atlantic seaboard, rises a clear 100km (60 mils) south of the High Atlas across the verdant Sous Valley, though at its east end the massifs of Siroua and Sarho merge their twisted barren slopes with those of the high Atlas. South of the last oasis villages of the Anti-Atlas the flat wasteland of the Western Sahara stretches immutably south; a harsh landscape that shows a 1000km (600 mile) face of savage cliffs to the Atlantic, broken by beaches at Tarfaya, Laayoune and Dakhla.

Moroccan landscape and the country's regional cultures are all extraordinarily diverse, but ultimately it is its people that prove most fascinating. In any one Moroccan there may lurk a turbulent and diverse ancestry: of slaves brought across the Saharan wastes to serve as concubines or warriors; of Andalusian refugees who came from the ancient Muslim and Jewish cities of southern Spain, and of Bedouin Arabs from the tribes that fought their way along the North African shore. All these peoples have mingled with the indigenous Berbers, who have continuously occupied the land since the Stone Age. The ruler of Morocco, King Hassan II, shares these influences, as well as being a direct descendant of the prophet Mohammed. He explains the peculiar temperament of his country by likening it to the desert palm: rooted in Africa, watered by Islam, and rustled by the winds of Europe.

It is a mistake to move too quickly around Morocco. Far too many visitors visit a city, suffer all the initial hassle and leave before they are relaxed enough to explore beyond the well-trodden list of major tourist sites. The frenetic energy, noisy animation, odours and ceaseless babble of the Moroccan street initially threaten to overwhelm a visitor. In morocco, however, do as the Moroccans do. Take things slowly, and catch the afternoon siesta in order to be fresh for the evening paseo. A certain wry but friendly sense of humour is all that is needed to cope with the anarchic but addictive lifestyle.

If you want an ideal introduction to Morocco, a suggested itinerary might begin with a flight to Agadir, which you would leave quickly to stay a night or two at the delicious hilltop village of Immouzer-des-Ida-Outanane, amid waterfalls, banana plantations and palm groves, before travelling east to the walled city of Taroudannt. From there you could cross the high Atlas at the Tizi-n-Test pass on your way to Marrakech. After a few days in this great city, move west again to the coast at the charming town of Essaouira, before moving down the southern coast to the desert gateway of Tiznit, on your way to a last few days' walking in the magnificent valleys of the Anti-Atlas around Tafraoute.

Barnaby Rogerson was conceived on a yacht and born in Dunfermline. He first fell in love with the idea of Morocco aged nine, standing before Delacroix's Arab Tax in Washington D.C.'s national Gallery. He first visited Morocco when he was 16, on an errand to buy fresh vegetables for his mother at the market in Tetouan. He has been going back ever since, but over the last twenty-one years has also found time to restore garden temples, lay pebble floors in grottoes and write a history of North Africa.