Clinical Pathway for Appendix Malignancy |

|

Figure 24 |

I. Introduction II.Principles

of Management III. Current

Methodologies for Delivery of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

IV. Clinical Results of Treatment V. Ethical Considerations

in Clinical Studies with Peritoneal Surface Malignancy VI.

References

IV. Clinical Results of Treatment

Reliable Relief of Debilitating Ascites

Patients with a large volume of malignant ascites are frequently encountered as a cancerous process moves toward its terminal phase. This may be caused by breast cancer, gastric cancer, mucinous malignancies of the colon or appendix, and primary peritoneal surface cancers. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is uniformly successful in eliminating the debilitating ascites (24,25). Success usually requires two or three instillations of a systemic dose of appropriate chemotherapy into the abdomen. Frequently combinations of both systemic and intraperitoneal chemotherapy are selected (Table 6). Also, Link and colleagues used mitoxantrone in this clinical situation.(26)

It is important to inform patients that intraperitoneal chemotherapy as treatment for malignant ascites is for symptomatic relief and should not be considered curative. The mass of solid tumor seen by CT scan will remain unchanged or will progress during treatment. Only the ascites will disappear. The mechanism of action of intraperitoneal chemotherapy on large-volume malignant ascites is destruction of surface cancer. This causes a layer of fibrosis over all malignant deposits and also on normal parietal and visceral peritoneal surfaces. This fibrotic layer of tissue prevents formation of both normal peritoneal fluid and malignant fluids. The fluid that had previously accumulated in the abdomen is directed by the layer of fibrosis into the circulation. After three or four intraperitoneal chemotherapy treatments the abdominal space may transiently cease to exist as peritoneal surfaces adhere together.

Technique for Chemotherapy Instillation for Treatment of Ascites

The technique used for repeated instillations of intraperitoneal chemotherapy to palliate malignant ascites is crucial for success. First paracentesis using a temporary all purpose drain should provide access to the peritoneal space. A long term indwelling (Tenckhoff) catheter should not be used to provide access because of the high incidence of infection with a foreign body located within a large volume intra-abdominal fluid over a long time period. Also an intraperitoneal subcutaneous port should not be used because of difficulties it creates with drainage of intraperitoneal fluid. Repeated paracentesis is safe if CT or ultrasound is used to select the site on the abdominal wall for puncture. When the ascites is gone or greatly diminished, the paracentesis becomes more dangerous. Of course, if the malignant ascites is greatly reduced then these treatments are discontinued.

Schedule and Dose of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Treatment of Ascites

The all purpose drain is kept in place for five days. Each day the ascites fluid is drained as completely as possible. Multiple changes in the patient's position may facilitate drainage. Then the intraperitoneal chemotherapy solution is instilled for 23 hours dwell. Our first choice of drugs is a combination of cisplatin (15mg/m2 /day) and doxorubicin (3mg/m2 /day) instilled as rapidly as possible. As soon as the chemotherapy solution has been instilled, the patient is instructed to turn from front to back and from side to side every one half hour. Alternatively mitoxantrone can be used at 3mg/m 2 / day for five days in a row. The cycle of treatments are repeated at 3 week intervals. In a few patients, persistent ascites may require a surgical procedure (debulking) in order to separate adherent bowel loops, remove bulk disease, and allow the use of a single cycle of heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. During the debulking, only large masses of tumor are removed. This generally includes the greater and lesser omentum and penduculated tumor masses. No attempt at a complete cytoreduction is made. The patient is treated for 90 minutes with heat, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. The responses achieved in patients that are debulked and then given chemotherapy may be more lasting than in patients given chemotherapy only.

Treatment of Mucinous Ascites

One caveat must be mentioned regarding the management of debilitating ascites. If the intraperitoneal fluid is mucinous, it cannot be drained through a tube. Relief of mucinous ascites can only be achieved by laparotomy and manual removal of mucinous tumor. Usually a greater omentectomy is performed as part of the debulking. Liposuction apparatus may greatly facilitate the complete evacuation of the viscous material. If the tumor mass can be reduced to a low level, then intraoperative and early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy may slow the re-accumulation of mucinous tumor.

Clinical Results of Treatment

Appendix Cancer and Pseudomyxoma Peritonei

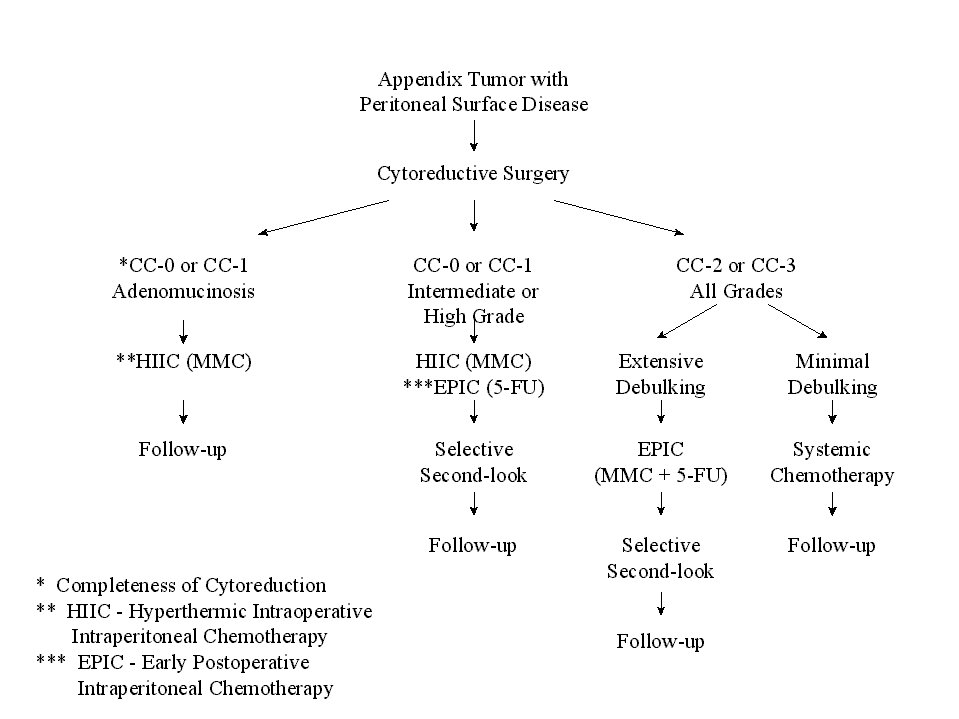

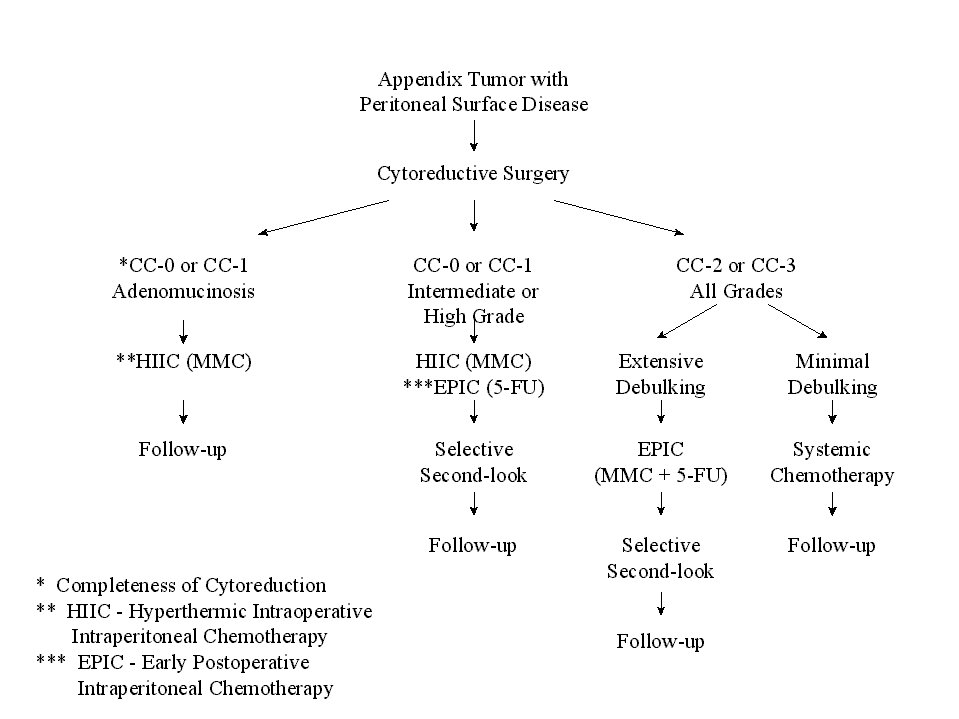

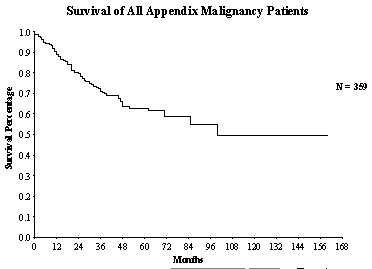

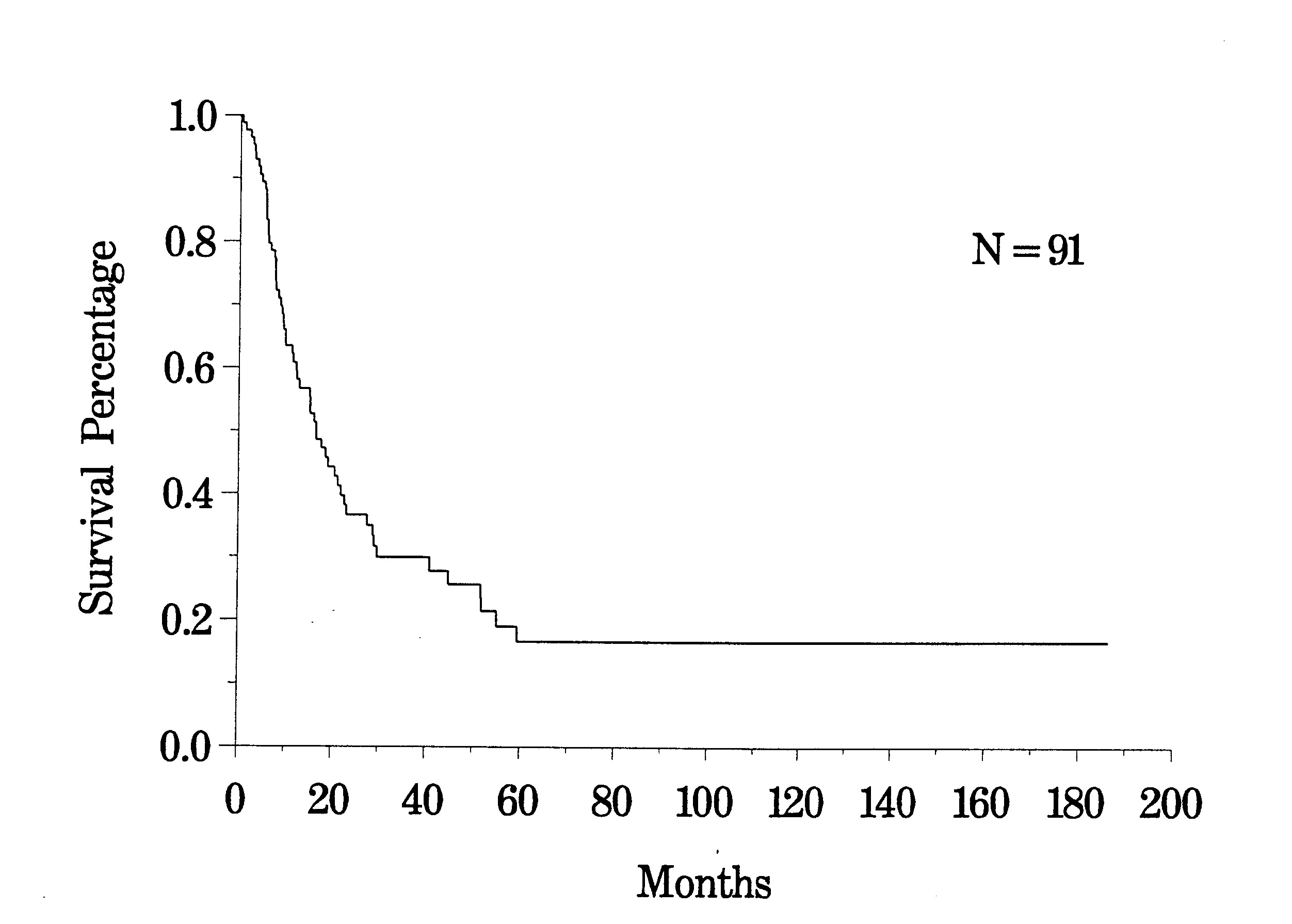

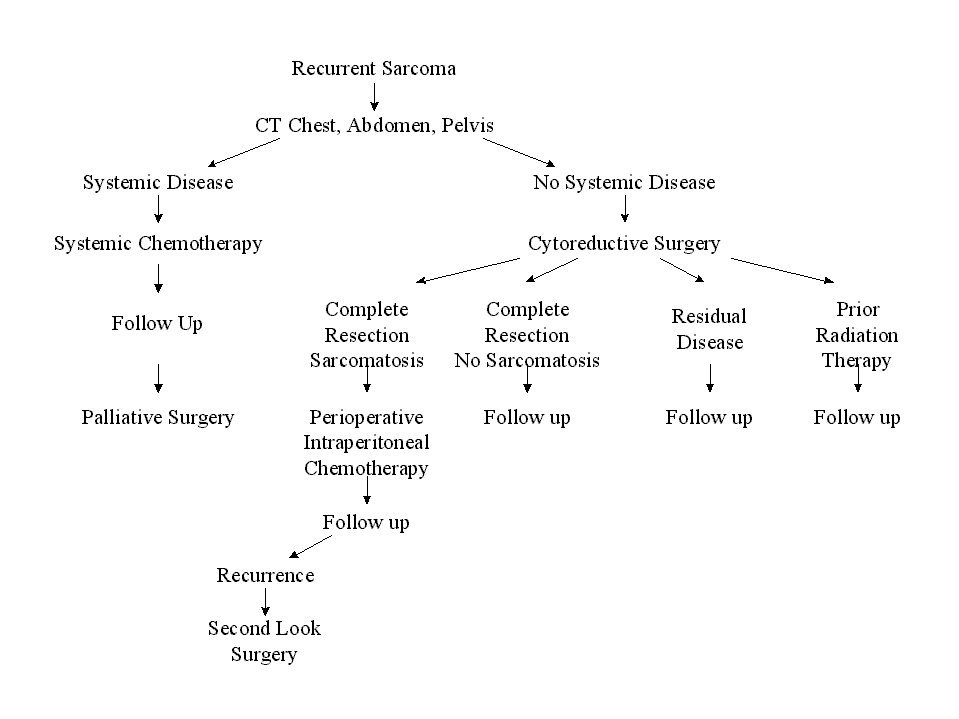

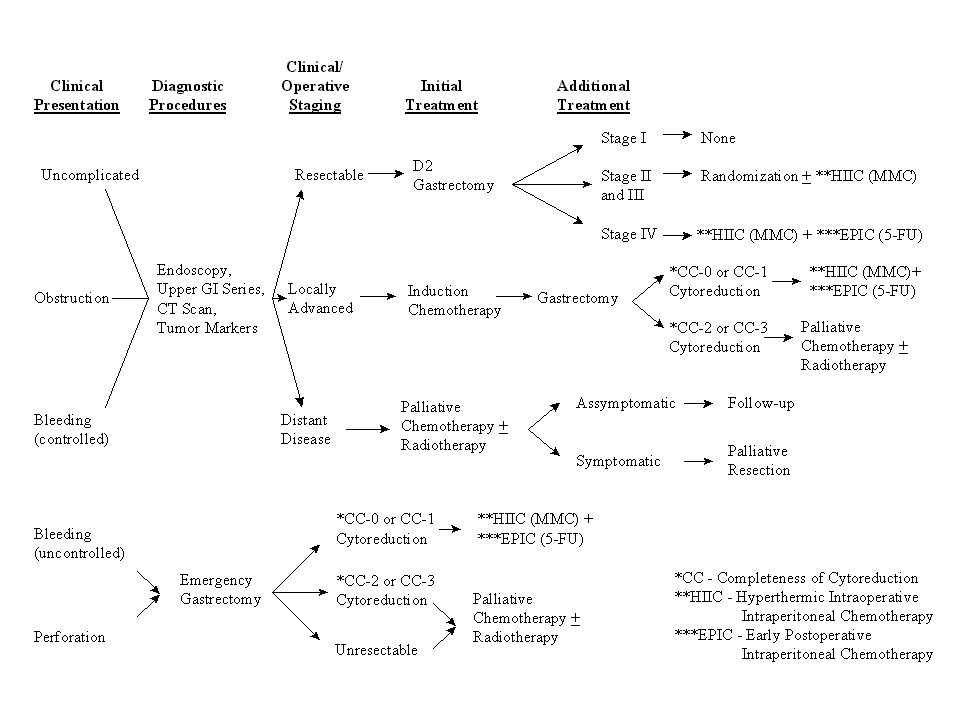

The paradigm for treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis is appendiceal malignancy. The experience with approximately 350 patients treated over a 15 year time span is presented in this manuscript. The clinical pathway currently utilized for appendix malignancy with peritoneal dissemination is shown in Figure 24. The survival of all patients is approximately 50% (Figure 25).

Clinical Pathway for Appendix Malignancy |

|

Figure 24 |

Survival of All Appendix Cancer Patients |

|

Figure 25 |

Appendiceal malignancy as a paradigm.

The concepts gained from treating peritoneal surface malignancy from an appendiceal primary tumors can be translated to other gastrointestinal cancers. There are unique clinical features of the appendiceal malignancies that have facilitated the rapid progress documented with this tumor. Spread from appendiceal tumors usually occurs in the absence of lymph node and liver metastases. The primary tumor occurs within a tiny lumen. Even small tumors early in the natural history of the disease will cause appendix obstruction and cause appendix perforation. This results a release of tumor cells into the free peritoneal cavity. The seeding of the abdomen occurs in almost every patient before lymph node metastasis or liver metastasis has occurred. Second, there is a wide spectrum of invasion in which these tumors exhibit. The ones that are minimally invasive can be totally resected using peritonectomy procedures to achieve a CC-1 cytoreduction. Third, the majority of these tumors are mucinous. The texture of the implants allows greater penetration by chemotherapy than with solid tumors. Finally, the malignancy disseminates so that all of its components are within the regional chemotherapy field. If the intraperitoneal chemotherapy is successful in eradicating the residual tumor on peritoneal surfaces, the patient will be a long term survivor. If disease persists after chemotherapy, the peritoneal malignancy will recur. In these patients the response achieved by the intraperitoneal chemotherapy determines the outcome; assuming, of course, that a CC-1 cytoreduction was possible.

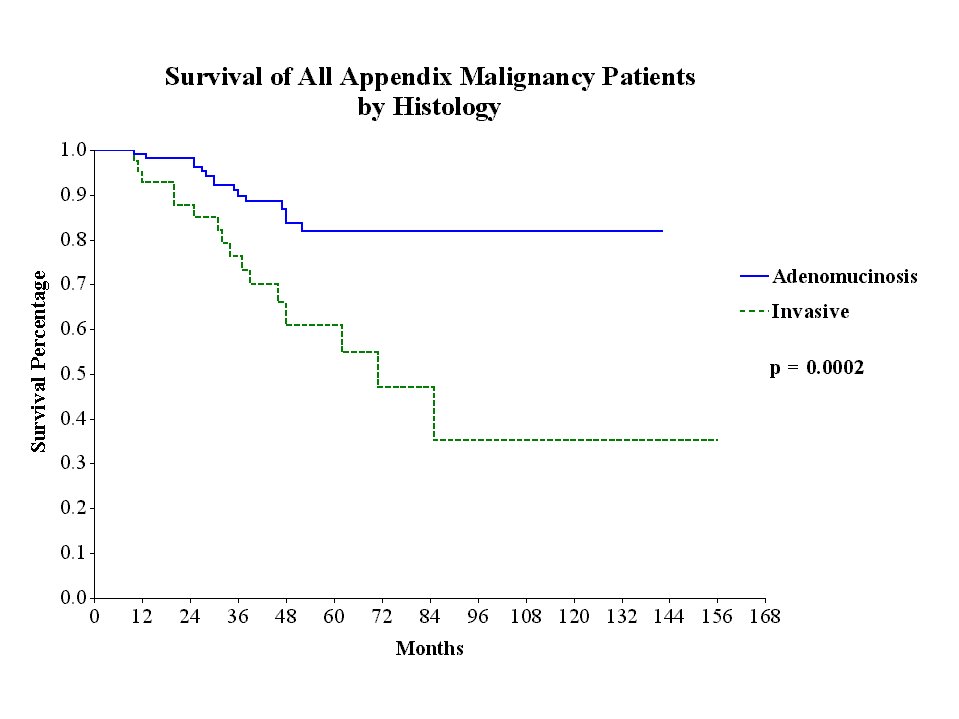

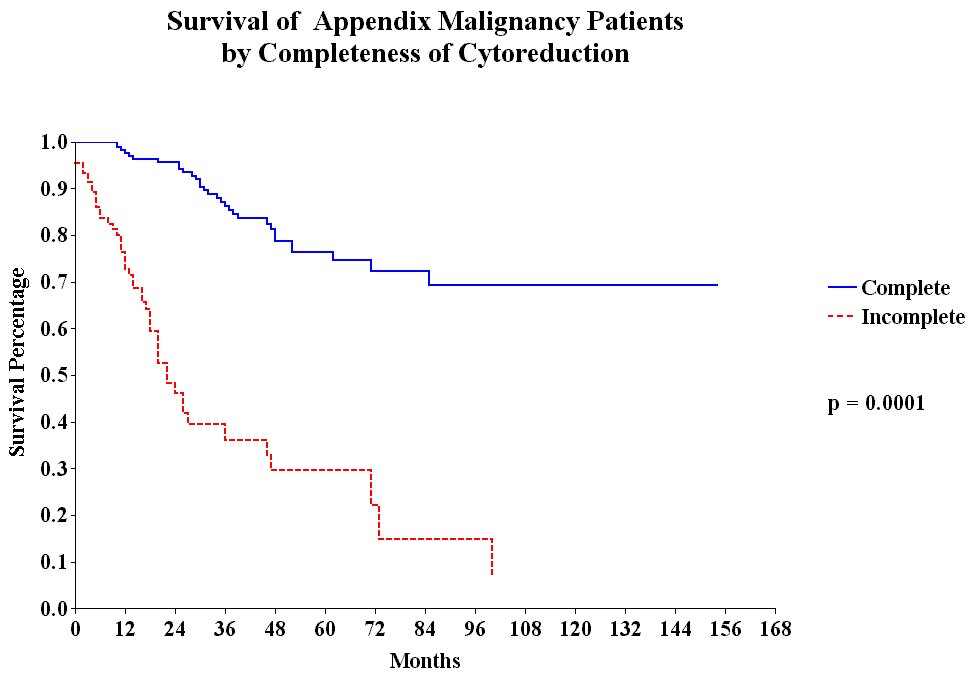

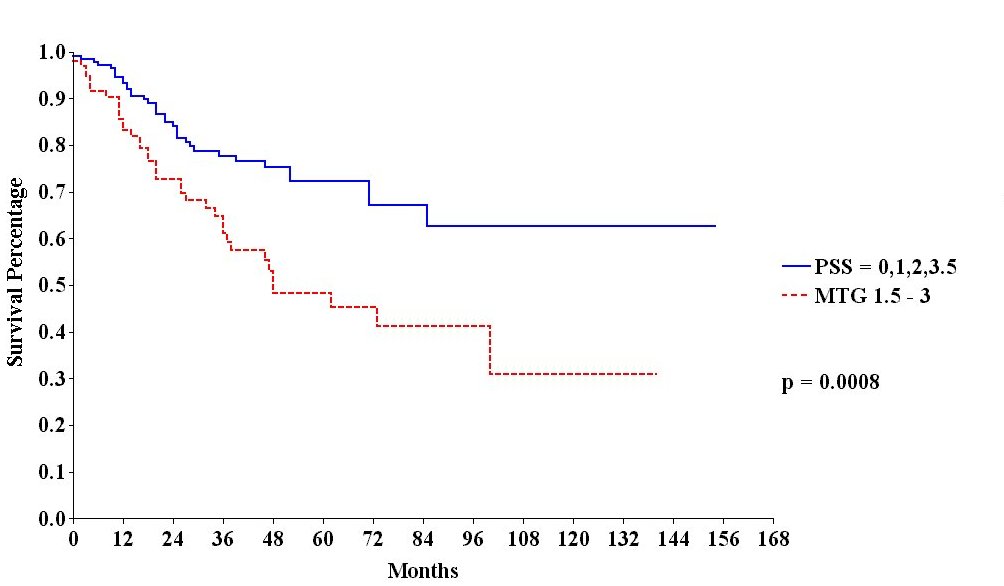

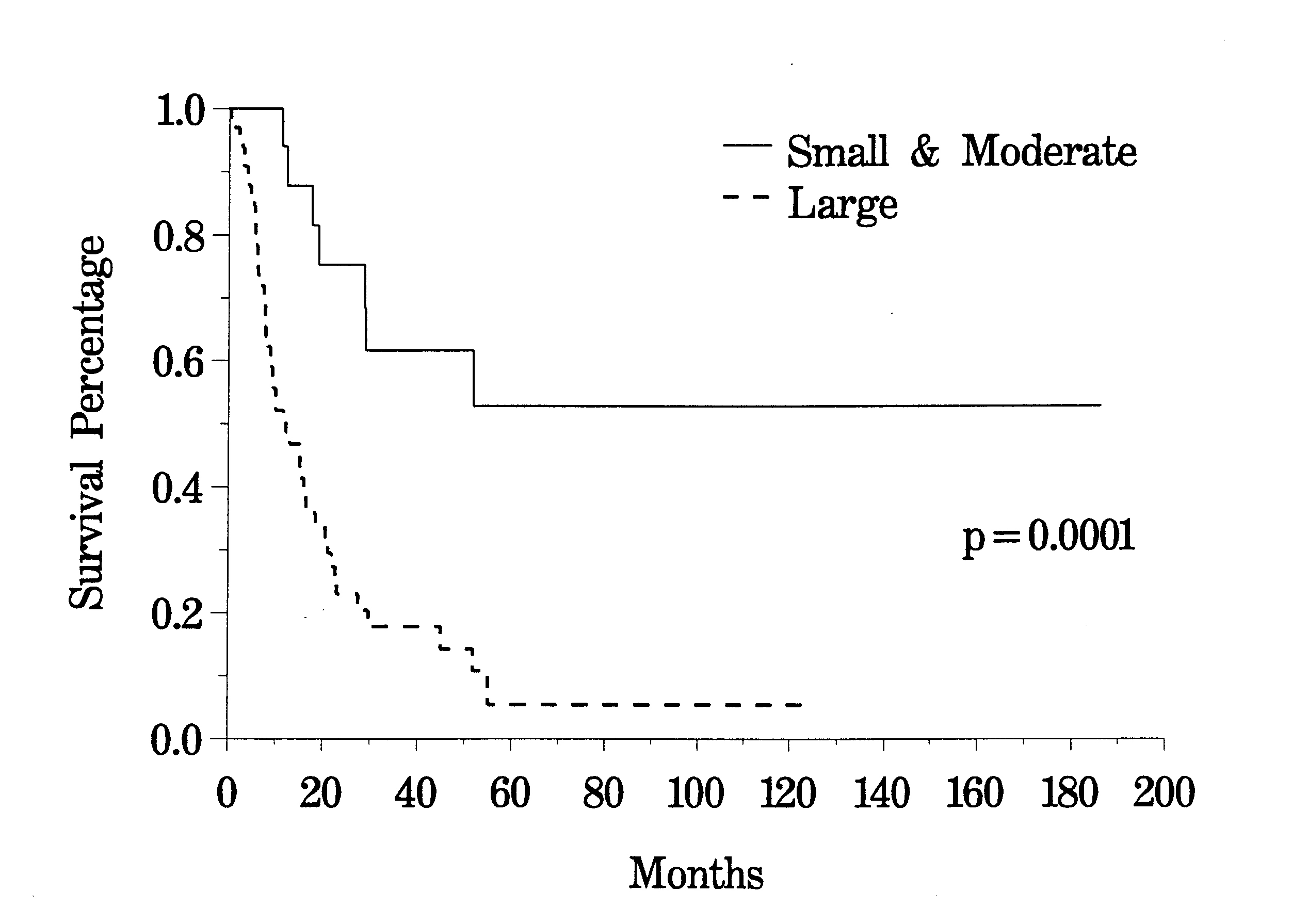

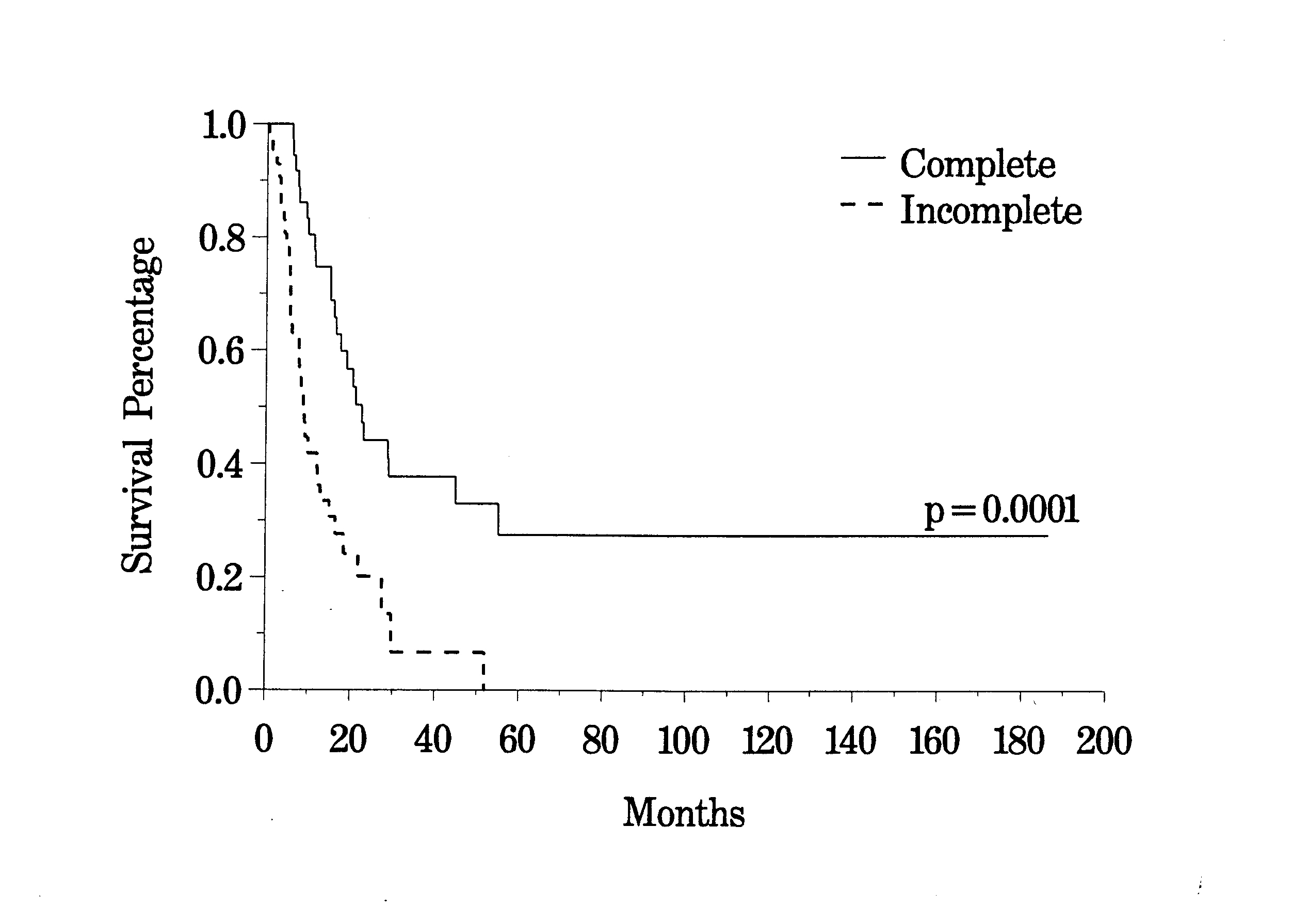

The treatment strategies used included peritonectomy procedures combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy with mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil. Survival was significantly correlated with the invasive character of the mucinous tumor (Figure 26), the completeness of cytoreduction (Figure 27) and the prior surgical score (Figure 28). In contrast to most studies with gastrointestinal cancer patients, lymph node involvement was not a determinate prognostic factor in patients with peritoneal dissemination of malignancy if intraperitoneal chemotherapy was used.

Survival of All Appendix Cancer Patients by Histology |

|

Figure 26 |

Survival of

all Appendix Cancer Patients by |

|

Figure 27 |

Survival of All Appendiceal Adenocarcinoid Patients |

|

Figure 28 |

Survival of

All Appendix Cancer Patients by |

|

Figure 29 |

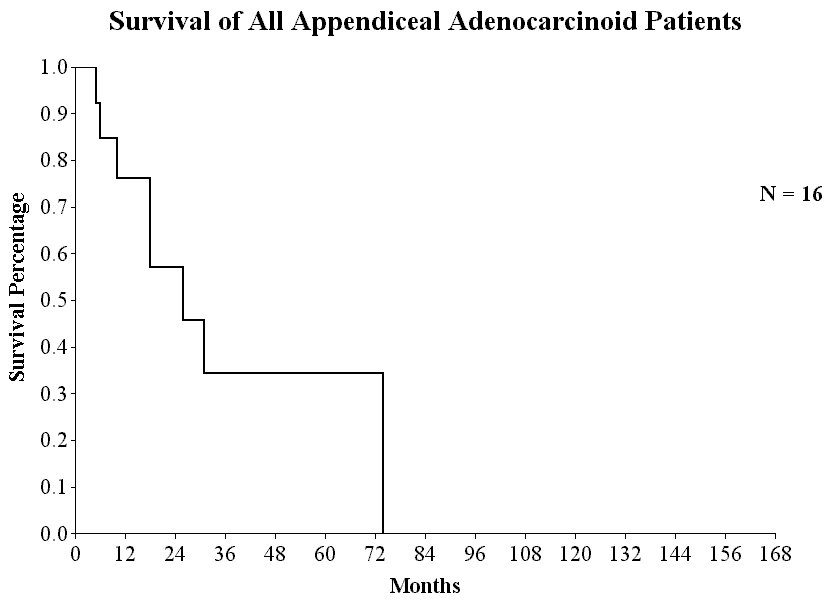

Although approximately 50% of patients with carcinomatosis from appendiceal malignancy survive long term with treatment, patients with an adenocarcinoid carcinomatosis from the appendix do not experience prolonged benefit from these aggressive treatments. Neither mitomycin C plus 5-fluorouracil nor cisplatin plus adriamycin have been effective (Figure 29).

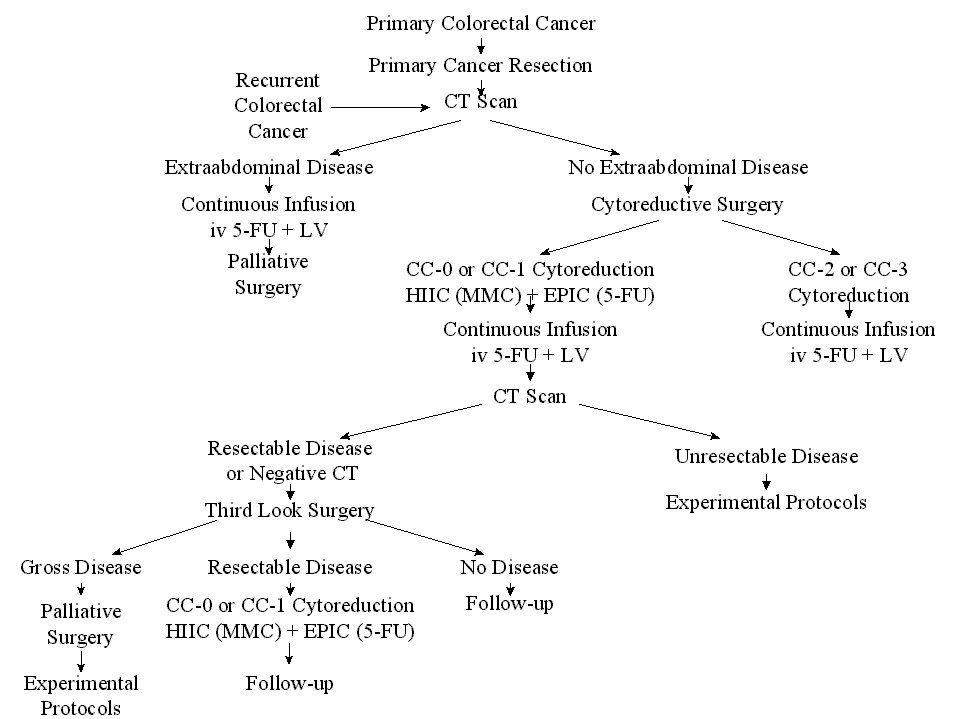

Colon Cancer Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

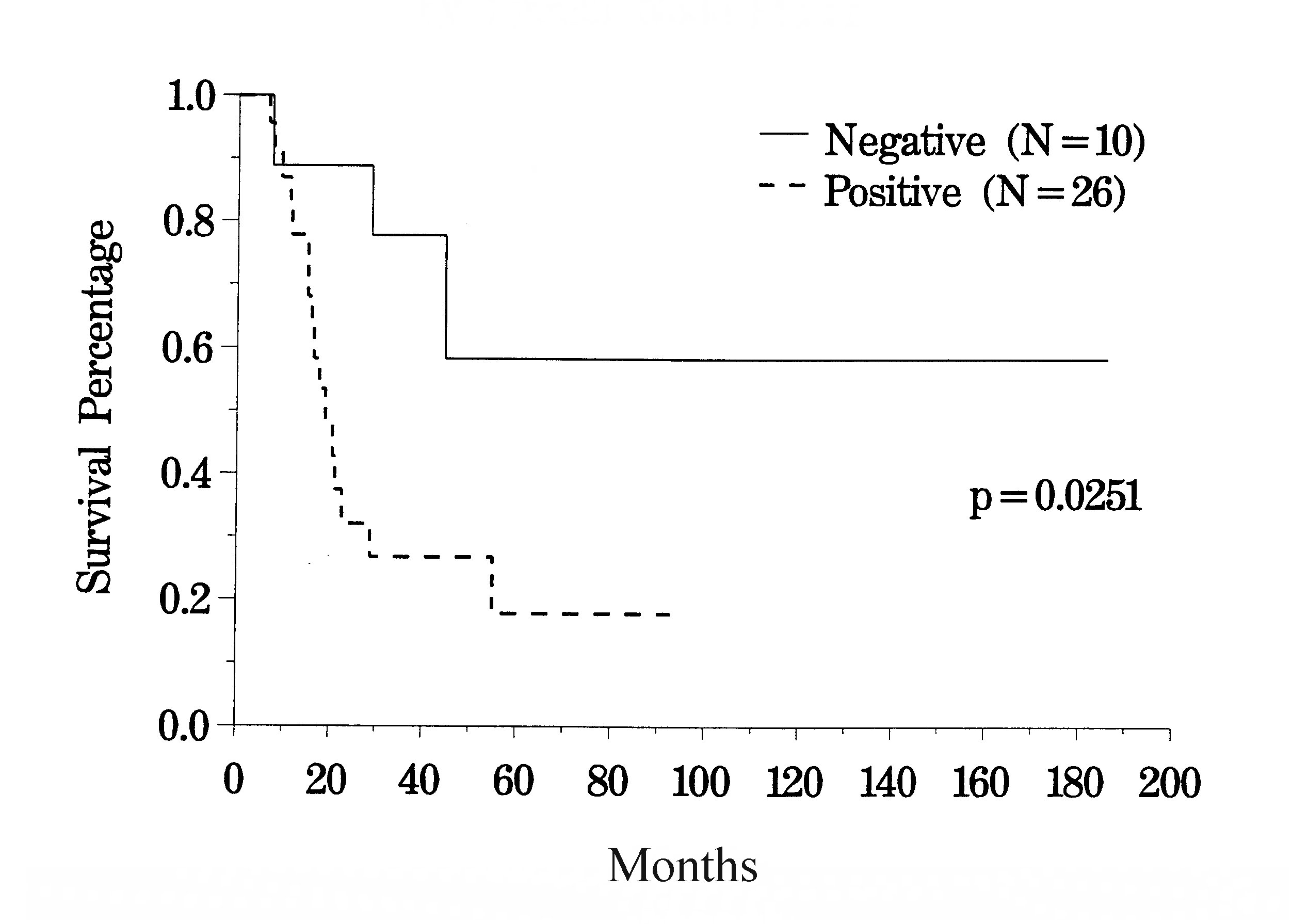

To date, approximately 100 patients have been treated who have peritoneal carcinomatosis from colon cancer. The clinical pathway currently utilized to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis from colon cancer is shown in Figure 30. The survival of all patients treated is shown in Figure 31. In this disease, the preoperative lesion size was a significant determinant of prognosis (Figure 32). The Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index should provide a score valuable in selecting patients for treatment. In patients who had a complete cytoreduction, there was marked improvement in survival; patients with residual disease show the expected short survival expected with peritoneal carcinomatosis from colon cancer (Figure 33). These data suggest an early aggressive approach to peritoneal surface spread of adenocarcinoma of the colon in selected patients. Patients with positive lymph nodes at the time of resection of the primary cancer have a reduced prognosis but approximately 15% may enjoy prolonged survival (Figure 34).

Clinical

Pathway for Peritoneal Carcinomatosis |

|

Figure 30 |

Survival of All Colon Cancer Patients |

|

Figure 31 |

Survival of Colon Cancer Patients by Lesion Size |

|

Figure 32 |

Survival of

Colon Cancer Patients by |

|

Figure 33 |

Survival of

Colon Cancer Patients with Complete Cytoreduction |

|

Figure 34 |

Clinical Pathway for Recurrent Abdominal Sarcoma |

|

Figure 35 |

Sarcomatosis

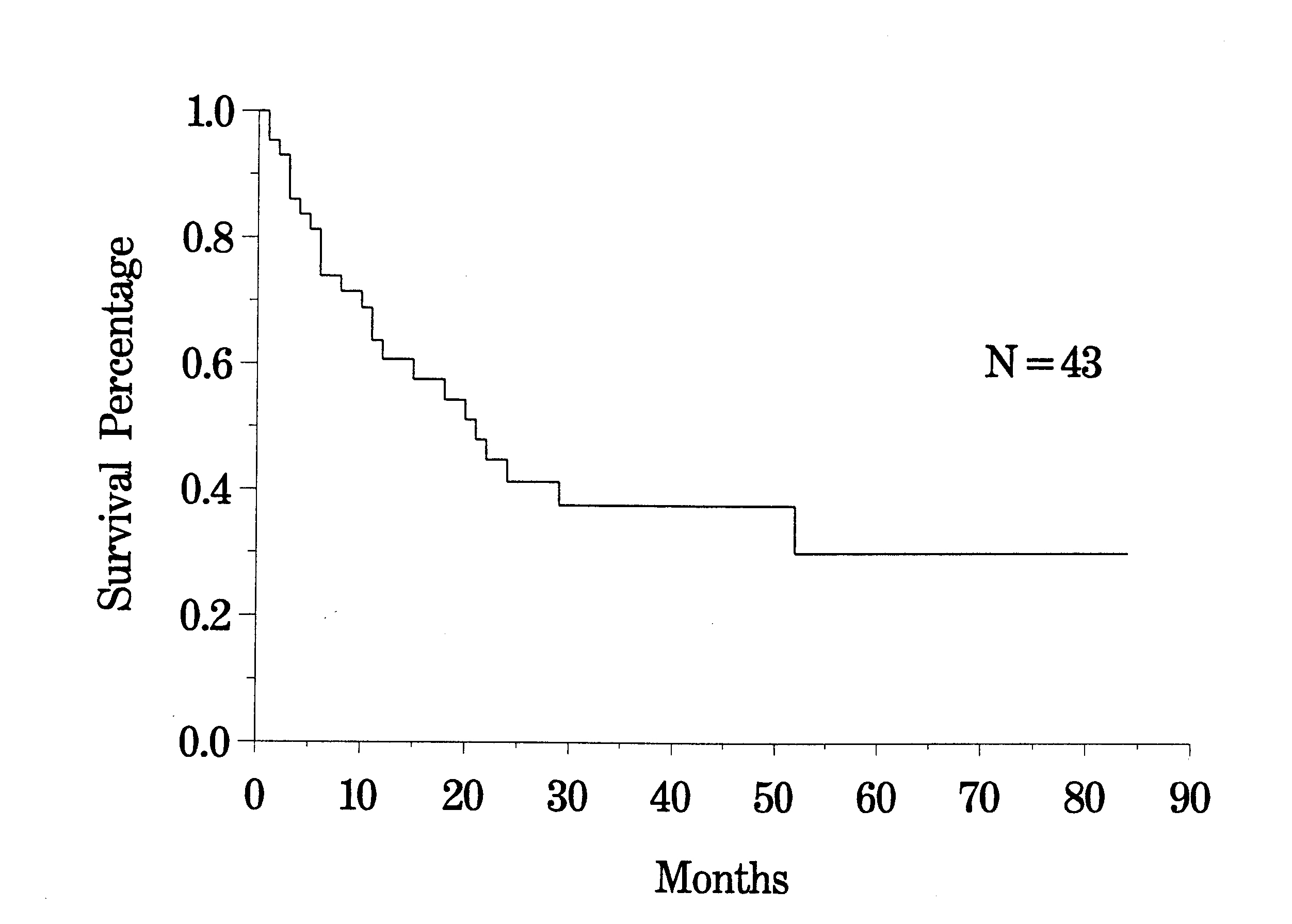

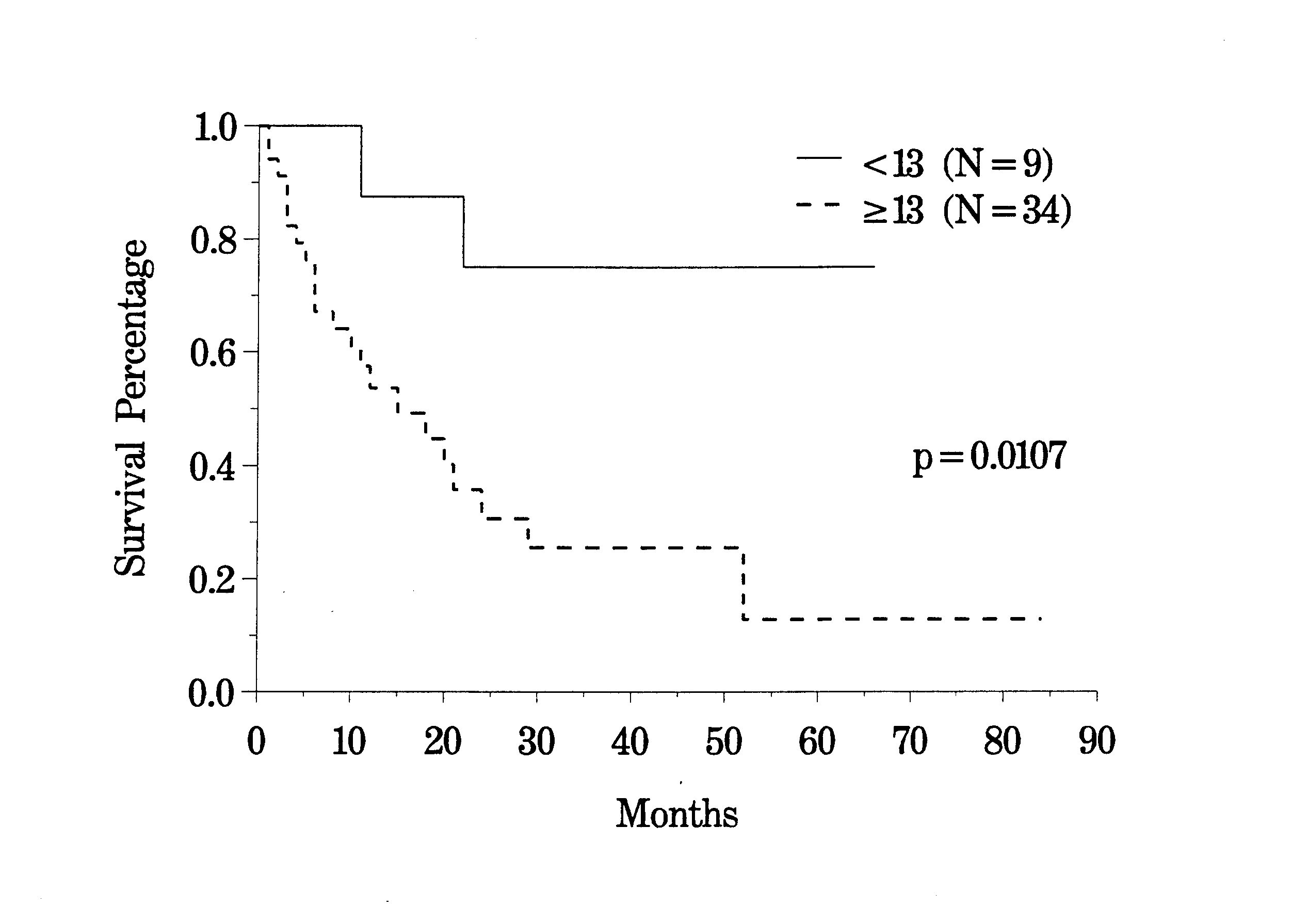

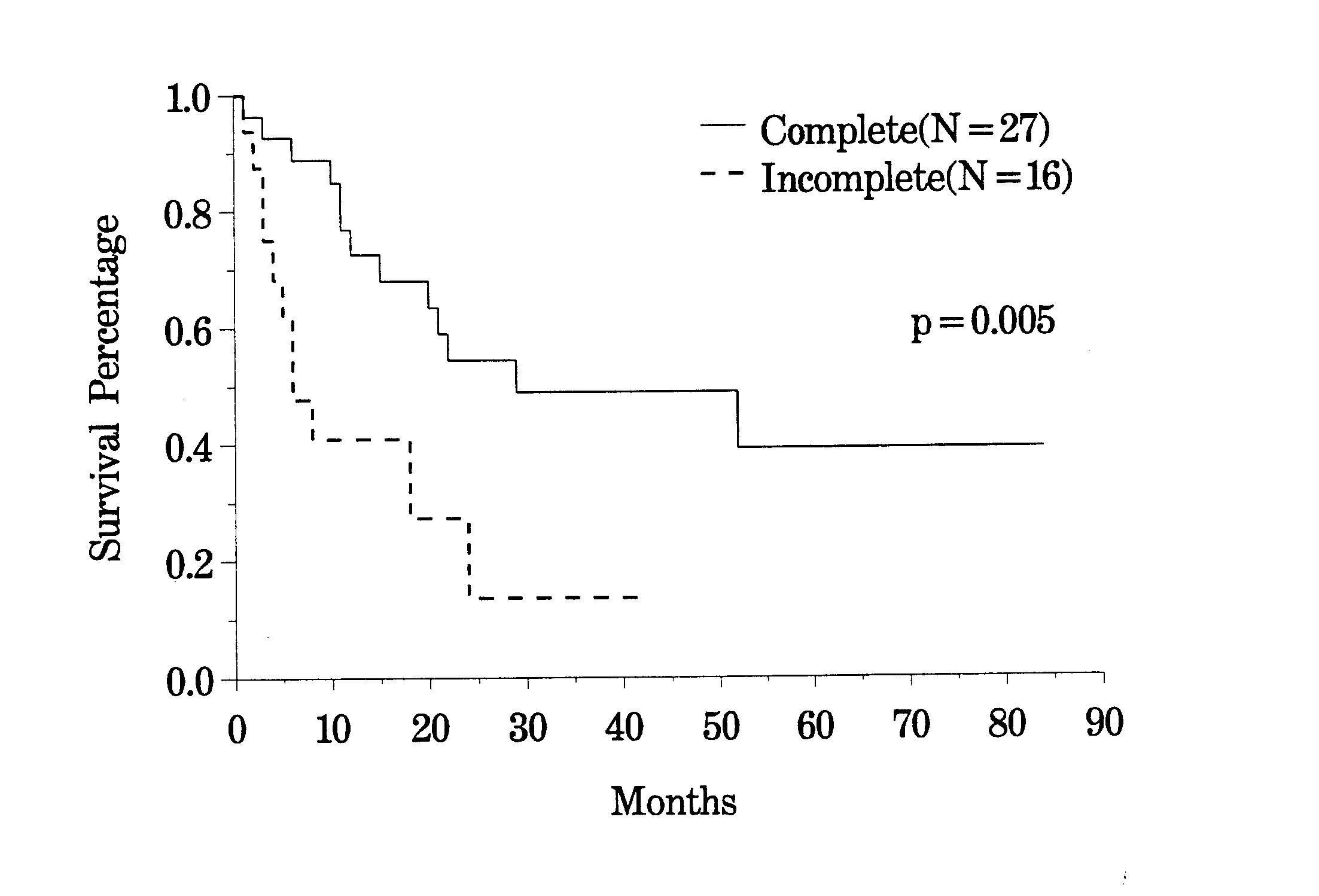

The clinical pathway currently utilized for patients with recurrent abdomino-pelvic sarcoma is shown in Figure 35. Berthet and colleagues have reviewed their experience with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for treatment of selected patients with sarcomatosis.(20) The survival of 43 patients with recurrent abdomino-pelvic sarcoma is shown in Figure 36. If the Peritoneal Cancer Index at the time of abdominal exploration was less than 13, there was a 75% 5-year survival. In those who had a Peritoneal Cancer Index of 13 or more, the 5-year survival was only 13% (Figure 37). The completeness of cytoreduction was also statistically significant for an improved prognosis. Twenty-seven patients with a complete cytoreduction had a 5-year survival of 39%. Sixteen patients with a CC-2 or CC-3 resection had a survival of 14% (Figure 38).

Survival of All Recurrent Sarcoma Patients |

|

Figure 36 |

Survival of

Recurrent Sarcoma Patients by |

|

Figure 37 |

Survival of

Recurrent Sarcoma Patients by |

|

Figure 38 |

Clinical Pathway for Gastric Cancer |

|

Figure 39 |

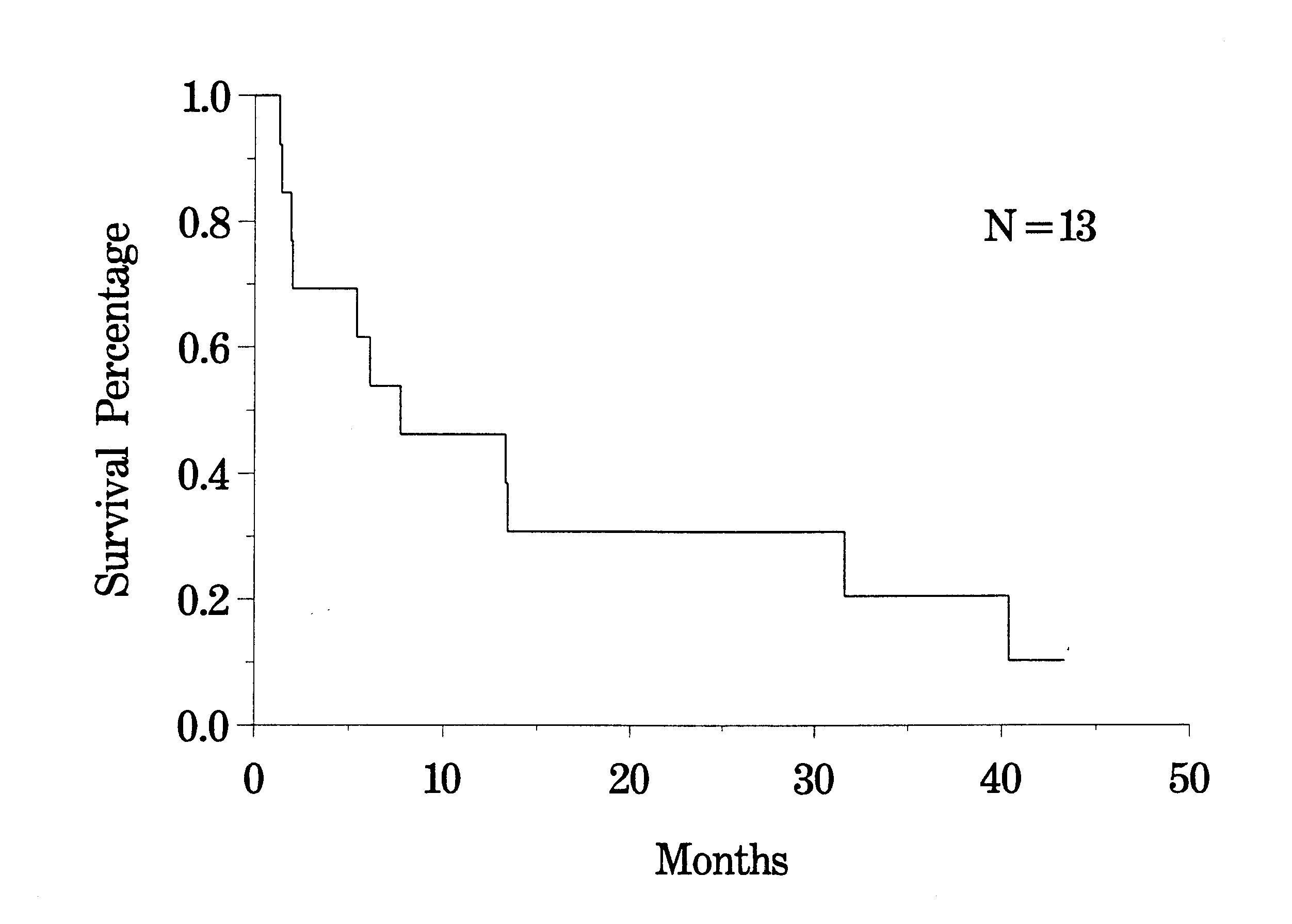

Peritoneal Seeding from Gastric Cancer

Extensive studies with peritoneal seeding from gastric cancer have been conducted in Japan. Prior reports from Western series are not available. Survival rates for patients in Japan with heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy at time of gastrectomy vary from 10% to 43%.(26,27) The clinical pathway currently utilized for gastric cancer is shown in Figure 39. Our results with resectable stage IV disease in 13 patients who received intraperitoneal chemotherapy are shown in Figure 40.

Survival of Resectable Stage IV Gastric Cancer Patients |

|

Figure 40 |

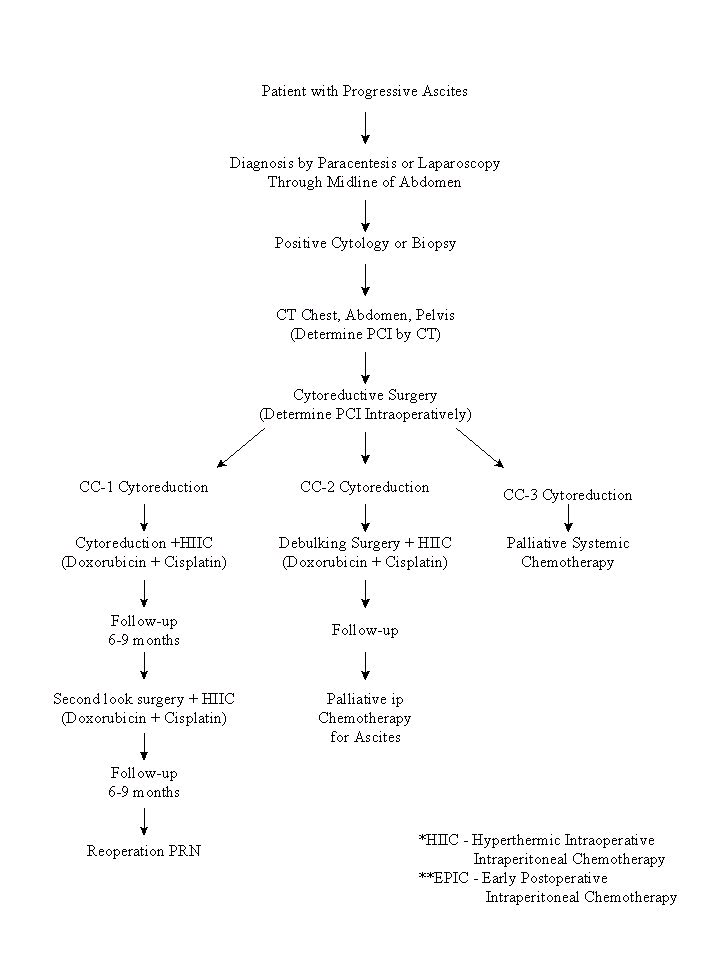

Clinical

Pathway for Primary peritoneal Surface Malignancies: |

|

Figure 41 |

Primary Peritoneal Surface Malignancy

A confusing and poorly understood group of tumors that have been successfully treated with peritonectomy and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy are the primary peritoneal surface malignancies. A clinical pathway currently utilized to treat peritoneal mesothelioma, papillary serous adenocarcinoma and primary peritoneal adenocarcinoma is shown in Figure 41. Currently, all patients are being treated with heated intraoperative cisplatin and doxorubicin. A second-look procedure with initiation of these same treatments is performed in six to nine months. As with appendiceal adenocarcinoma, the survival was heavily dependent upon the invasive character of the tumor and the completeness of cytoreduction. The median survival in a group of 44 patients with primary peritoneal tumors was 18 months (Figure 42). Further experience with this group of patients is necessary.

Survival of All Primary Peritoneal Surface Malignancy Patients |

|

Figure 42 |

Recurrent and Obstructing Gastrointestinal Cancer

Averbach and colleagues looked at their experience with an extremely problematic group of patients. These are patients who developed intestinal obstruction after prior treatment for a gastrointestinal malignancy. With aggressive treatments using a second-look surgery, peritonectomy procedures, and intraperitoneal chemotherapy, a complete cytoreduction resulted in a 5-year survival in 60% of the patients, and an incomplete resection resulted in no 5-year survivals. The patients with appendiceal malignancy had a greatly improved survival as compared to those with colon cancer or other diagnoses. A free interval of greater than 2 years between primary malignancy and the onset of obstruction also correlated favorably with prolonged survival. Only patients with intraperitoneal chemotherapy used in conjunction with cytoreductive surgery were shown to have prolonged survival.(29)

Morbidity and Mortality of phase II studies

The morbidity and mortality of 170 consecutive patients who had cytoreductive surgery and heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis has been reported.(30) In these patients, there were three treatment related deaths (1.8%). Peripancreatitis (7.1%) and fistula (4.7%) were the most common major complications. There were 25.3% of patients with grade III or IV complications.

Alternative Approaches

Peritoneal carcinomatosis has been treated in the past with systemic chemotherapy. No long-term survivors have been described in the literature. Palliative surgery can give temporary relief of intestinal obstruction. These efforts have always been categorized as low value surgery because long-term survival was rarely achieved. Other therapies that would include intraperitoneal immunotherapy, intraperitoneal isotopes, and intraperitoneal labeled monoclonal antibody have not shown reproducible beneficial treatments. In summary, alternative approaches to cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis have not been reported.

Patient Care Considerations

The major detrimental side effect of combined cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy is prolonged ileus. Patients may have a nasogastric tube in place with large volumes of secretions being aspirated for two-to-four weeks postoperatively. The length of time required for nasogastric suctioning is dependent upon the extent of the peritonectomy procedures and the extent of prior abdominal adhesions that required lysis.

The most life threatening postoperative complication is the fistula. These are almost always sidewall perforations of the small bowel but colon and stomach perforations have occurred. Patients need to be made aware of the possibility of a fistula before cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy are contemplated. As mentioned above, the anastomotic leak rate is low.

Following these treatments, the patient is maintained on parenteral feeding for two to four weeks. Approximately 20% of patients, especially those who have had extensive prior surgery or who have a short bowel, will need parenteral feeding for several weeks after they leave the hospital.

I. Introduction II.Principles

of Management III. Current

Methodologies for Delivery of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

IV. Clinical Results of Treatment V. Ethical Considerations

in Clinical Studies with Peritoneal Surface Malignancy VI.

References